Rachel Sadoff AB '21

Watching a presentation at the "Kickoff of Sri Lanka's SUN [Scaling Up Nutrition] Business Network." About 50 attendants from the government, private sector, and international organizations joined this conference (which I co-coordinated through WFP Sri Lanka) to brainstorm collaborations that might improve national nutrition and make long-term plans to do so (Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2019)

I grew up in five countries across Europe and Asia because of my parents’ work, and I saw a lot of startling health disparities along the way. I was inspired by their impact, and that’s a key reason why I want to go into global health. I lived in America (DC) until I was 8, and then spent 2 years in Switzerland, 3 in Nepal, 1 in Thailand, and 3 in Italy, making me an Italian international student at Harvard. Our most startling move was from Geneva to Kathmandu, which was the poorest country in the world outside Africa at the time. I remember the bus ride to school was over the Bagmati River, which was very muddy and seriously polluted by the time it reached Kathmandu. There were lots of remnants of cremations tossed into the river along with sewage, and I remember thinking it smelled like eggs. I also remember seeing flies gathering around butchered goats in street-facing shops throughout the day. All of these environmental factors devastated the health of the people who lived along the Bagmati.

And I remember thinking, ‘these people are just as nice as the people in Switzerland, just as smart and kind and aware of what’s bad for them.’ I found it all so upsetting and confusing.

When I got to Harvard, it became clear to me that I was terrible at math. I came here wanting to be an engineer, but realized that my real strengths, the best things I could offer the world, were my writing and communication skills. So I decided I would need to find a way to contribute to international development with words.

I was drawn to the History and Literature department because I loved the idea of using different kinds of media to learn about human nature. I studied a lot of war movies, sociology, and journalism, which also strengthened my passion for advocacy. During the COVID pandemic, I’ve also come to appreciate how people can structurally misinterpret science, which affects real people, like by persuading millions of people to not get the vaccine. So how can you explain scholarly journal articles to people who don’t understand them? That’s one place I’d love to contribute as a public health communicator. It’s also crucial to bring in diverse perspectives to these conversations -- it’s the best way to get a nuanced sense of cultural factors and sensitivities. I also think you can contribute by crafting comprehensive plans and policies that may or may not be adopted - say, the Green New Deal, which has been called extreme, but it gives us a sense of where to start.

If I’m able to put together a plan to fight tuberculosis that’s similarly ambitious, the international community will at least have some reference points for attainable interventions. I’d be perfectly content putting a tiny dent into big initiatives like those.

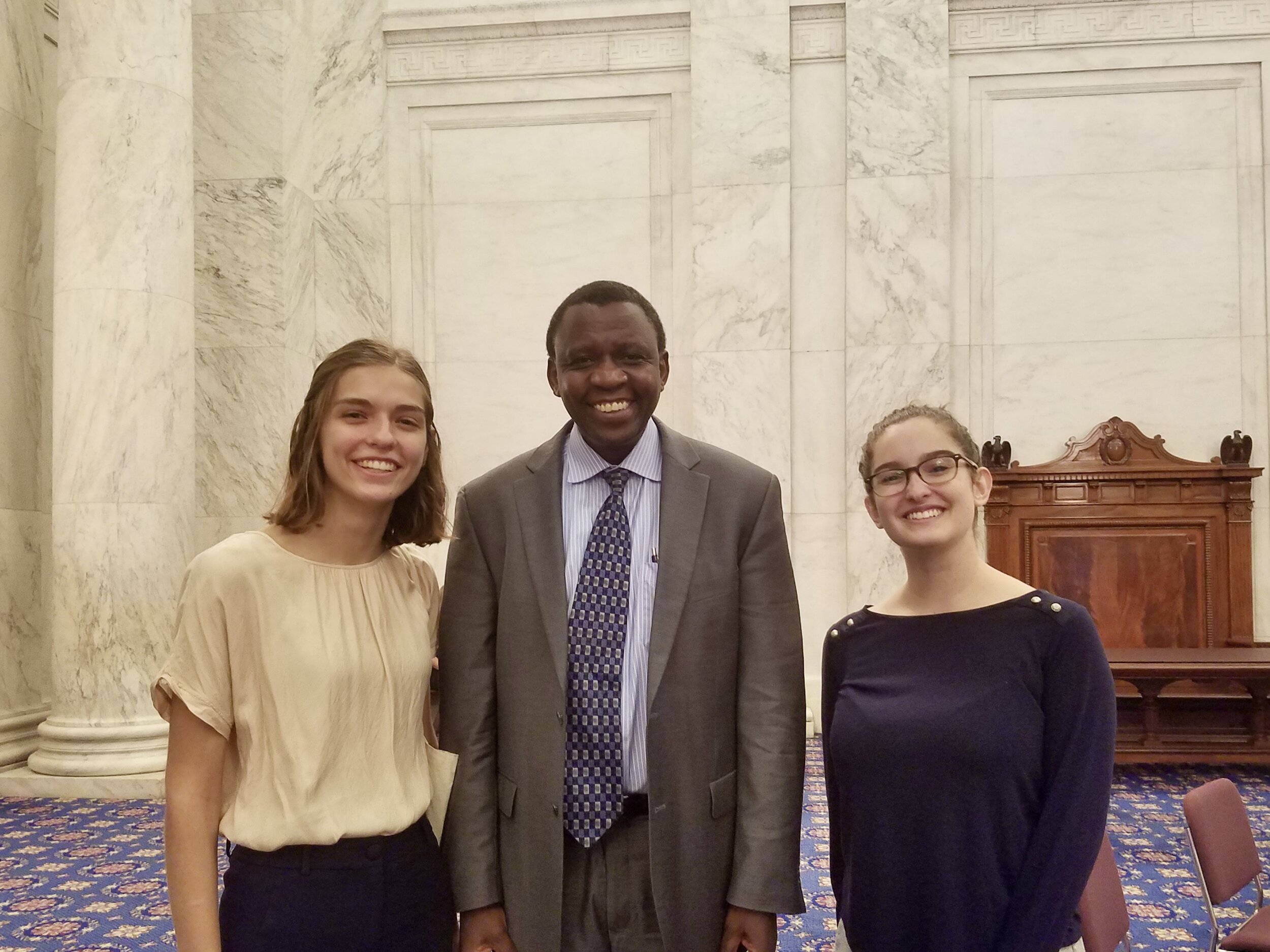

Representing Friends of the Global Fight Against AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria at "15 Years of PEPFAR: Past Success and Future Progress" (Washington DC, 2018)

I think I am most passionate when I am driven by fury and indignation. I think it is a moral failing that TB is still a pandemic, and we know how to fix it, have the money to fix it, and have plenty of expertise and resources to draw from. But people are still dying - three people die of TB every minute. It’s the leading infectious disease killer, but oftentimes key resources are diverted to other causes. TB affects everyone, but it’s a disease of poverty that’s notorious for killing vulnerable populations.

Countries that tackle multiple epidemics often deprioritize TB, and I find it hard to understand because TB programs are just as expensive, urgent, and effective as those of other epidemics. TB is not a mystery. We know everything about it, and that contributes to the problem.

There are no new variants, no big headlines, no developments in TB generally, so it can be hard to generate or sustain public interest and attract donors for research and programming. Also, many of the places where it’s prevalent tend to stigmatize it as impure, or gross, or a product of a patient’s irresponsibility. Unfortunately, it’s also often comorbid with other stigmatized diseases like HIV/AIDS. The treatment regimen can be long and hard, and often patients don’t have the resources to advocate for themselves or spread awareness about their needs.

(Single-handedly) manning the WFP booth at the national World Health Day fair in the Arcade of Independence Square (Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2019)

I’ve cried two times this past year out of joy. First, when I was assigned my advisor for my thesis, and second, when I was assigned my advisor for my independent study in Global Health and Health Policy. They were, respectively, Dr. Lauren Kaminsky and Dr. Salmaan Keshavjee. They are both geniuses and so sensitive, insightful, patient, and supportive. I feel challenged and embraced by them. Harvard faculty are world-renowned in their fields, so they might just sit on their laurels and not take interest in their students. But others, like my advisors, genuinely care about and support student’s work -- they’ve been golden. Some advice for first-years and sophomores: try everything and find what inspires you, not what you think is going to advance your career. I stumbled into my favorite extracurricular, Effective Altruism (their motto is ‘doing good better’), because they said they had a fellowship with a time commitment of just a few hours per week, but I’ve been hooked ever since, and it’s opened doors for me personally and professionally -- I’m giving international presentations and I’ve found some of my best friends through the group. I didn’t join Effective Altruism because I thought it would look good on a law school application, but because I was ready for thought-provoking conversations. It’s also sometimes counterproductive to sign up for something that you think will help you long term - I thought law school was my calling for years, and so I joined a club that was designed exactly for that - a pipeline into law school. I was miserable, and even in terms of my motivation for joining, not the best use of my time and energy.

So, explore and pursue what you are genuinely interested in!

Rachel Sadoff (they/them)

Concentration: History and Literature

Secondary: Global Health and Health Policy

Citation: Italian

Class of 2021

Interviewed and Compiled by Felicia Ho

![Watching a presentation at the "Kickoff of Sri Lanka's SUN [Scaling Up Nutrition] Business Network." About 50 attendants from the government, private sector, and international organizations joined this conference (which I co-coordinated through WFP …](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56f0c5eb45bf216c52238331/1616470153220-U944Y9UNPRKXOYRJWN6L/2.jpeg)